Below please find a few words I delivered to introduce the closing plenary of a seminar last week. It’s short but says something about what it’s like for humanities professors trying to help run departments, divisions, or colleges during the worst assault on higher education this country has ever seen.

Association of Departments of English/Association of Language Departments Summer Seminar 2025, New York University

Plenary V and Closing: Doing the Good Work in Uncertain Times

Good afternoon and thanks for sticking it out. I’m Sam Cohen, of the University of Missouri and the Executive Committee of the ADE, and I will be your presider this afternoon. I’ll begin by briefly introducing our speakers; then, after a few words from me, we’ll have opening remarks from them and then discussion.

Our speakers: Amy Woodbury Tease from Norwich University; Gillian Lord from the University of Florida; Beth Howells from Georgia Southern University; and Reginald Wilburn from Texas Christian University. Please see the resource document thingie for their bios (not now!).

I’d like to start us off with a little local history. And there’s a lot of it right on this block: The Silver Center was built (under the name Main Building) in 1892 on the foundation of the original 1835 Gothic revival building that stood here; its first five floors for decades housed the American Book Company, a textbook concern most famous for publishing the McGuffey Readers, which taught generations of Americans how and what to read; the Brown Building of Science, to our east, stands on the site of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. That’s a lot of history for one block, which is not uncommon in New York, a city known not so much for preservation as for development, unfortunately emblematized lately by a particular national figure.

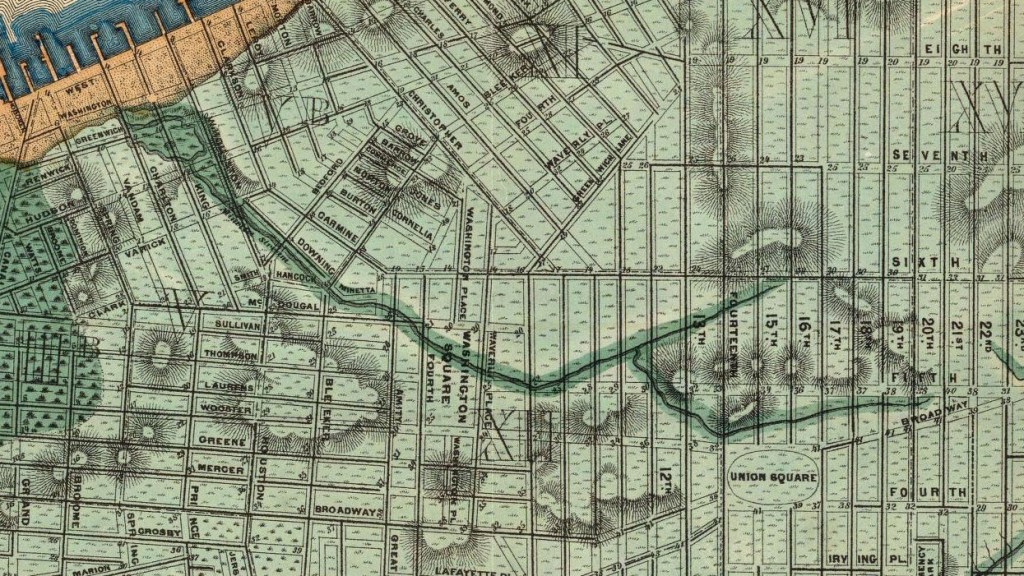

But the particular piece of very local history I want to focus on is the creek that used to run through the land on which Washington Square now stands, just to our west, Minetta Creek. It had two sources, one running south from what is now Fifth Avenue and 21st Street, just south of the Flatiron Building, the other beginning at Sixth Ave and 16th St, the two meeting at Fifth and 11th, just north of the park, and heading downtown and west to eventually empty into the Hudson. What makes this history interesting is what happened to the creek in the development of Manhattan from its pre-New Amsterdam state—before it was sold to Peter Minuit by the Canarsee, a group of Lenape Indians who neglected to tell him that they only occupied a small part of it. (So the story of that sale, usually told so the natives look like they got rooked—they only got twenty-four dollars-worth of beads and trinkets!—could also be told as the tale of Manhattan’s originary shady real estate deal.)

Minetta Creek was covered over in the 1820s, as the area through which it ran was developed, the potter’s field on its east bank closed and converted to a military parade ground and finally a park. But for decades the creek continued to run underground, popped up under West Village basements, could be traced, some said, by patterns of illness among residents under whose buildings it ran. There are at least two buildings in the neighborhood that house fountains that a hundred years ago filled with bubbled-up creek water. Whether it still runs under the streets is a mystery, but there are people who still look for it, drawn by the history and the mystery, maybe even attracted by the rich metaphorical possibilities of a hidden underground river running beneath a city.

Our speakers are here this afternoon, as our title says, to talk about doing the good work in uncertain times. I bring up the story of Minetta Creek to introduce this closing discussion because rather than focusing only on the uncertain times that are making the doing of the good work more difficult than the usual difficult, I’m hoping that we can talk more about the good work, and thinking about the story of the creek might help us do that, and I also just really like the story. I like it because the existence of a mysterious underground river appeals to me naturally but also because it appeals to me as someone trained in literature and writing. This creek is almost too much metaphor—it can stand in for the underlying forces of history, the costs of modernity, the unconscious and other subtexts. It’s even a metaphor for metaphor—for meaning-making. The good work we do is about many things, including of course the future employment for which study in literature and language (and folklore and history and art history and religion) prepares our students, but beyond that—beneath that—it’s about the work we help our students and faculty do to make meaning, to close read the world to see how it works and how it could work differently. It’s about a different kind of development, the development of individuals and communities through knowledge. It’s about insisting on these things against the things—like overemphasis on career, on the promises of technology, on the bottom line—that threaten to drive this good work underground.

So I’m opening this closing with a metaphor, which, like all metaphors, you can take or leave. But please join me now in listening to the ideas for doing the good work that our speakers, out of whose way I will now get, will offer, and in continuing the discussion they’ll begin.