In case you missed it, book banning is going national.

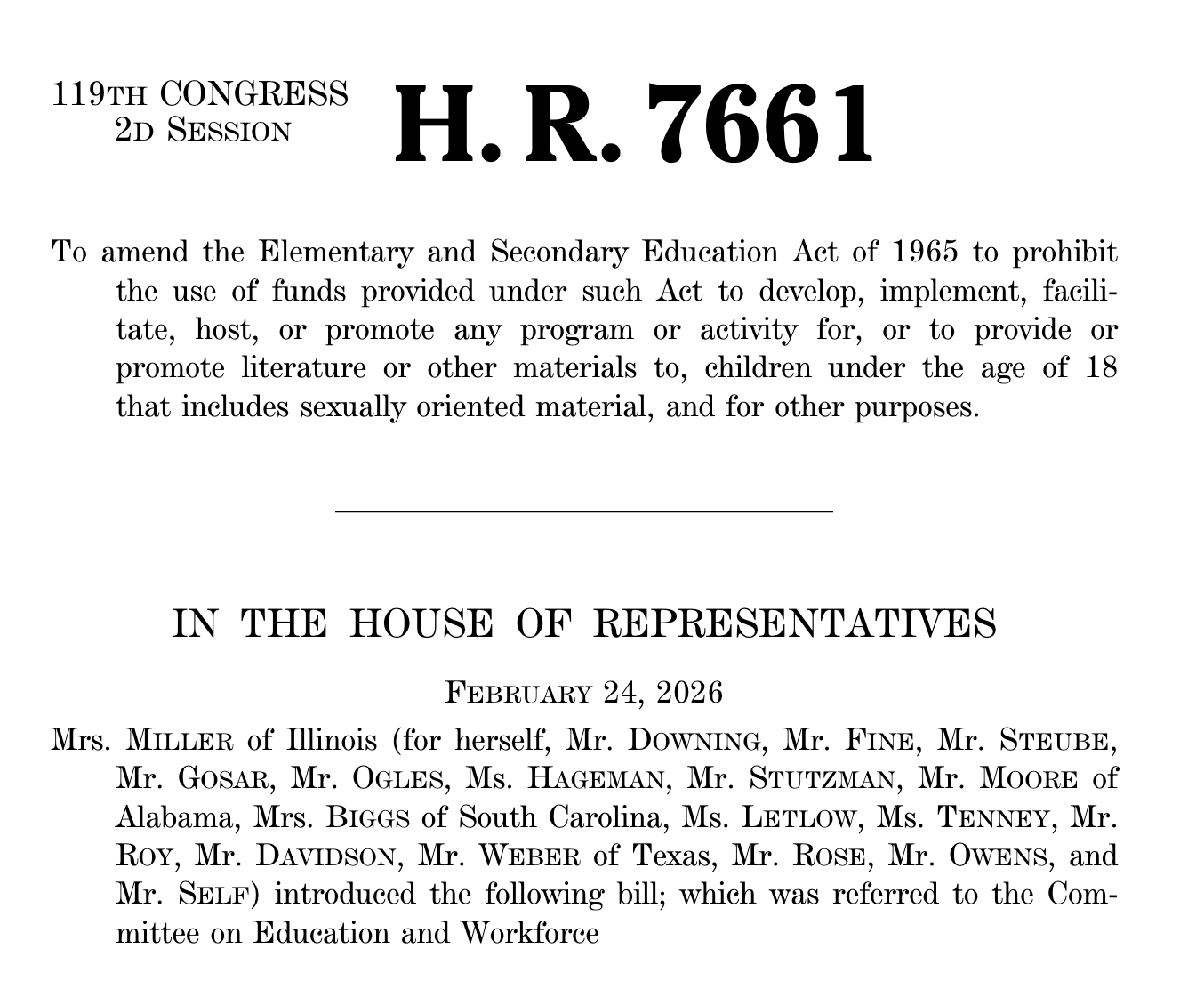

On Tuesday, February 24, HR 7661 was introduced in the second session of the 119th Congress by Rep. Mary Miller, the representative from the 15th, the most Republican district in Illinois. Rep. Miller is known for, among very few other things, quoting Hitler approvingly to a meeting of a conservative group called Moms for America, two days into her first term in 2021, in a way that’s worth reading in full:

“Each generation has the responsibility to teach and train the next generation. You know, if we win a few elections, we’re still going to be losing unless we win the hearts and minds of our children. This is the battle. Hitler was right on one thing: he said, ‘Whoever has the youth has the future.'”

In March of that same year, Miller introduced a bathroom bill, because the way to the heart of the youth is through making sure they hate trans people, apparently.

This past February, she misgendered Rep. Sarah McBride, recognizing “the gentleman from Delaware, Mr, McBride.”

(She’s also known for posting last spring about her outrage that a Muslim cleric was allowed to lead the House of Representatives’ daily prayer, writing that it was “deeply troubling that a Muslim was allowed to lead prayer in the House of Representatives this morning. This should have never been allowed to happen. America was founded as a Christian nation, and I believe our government should reflect that truth, not drift further from it.” She later corrected her post when she was informed that the cleric she thought was a Muslim was actually a Sikh, and then deleted the post entirely. But this is about a different kind of bigotry than anti-LGBTQ+ bigotry, so it is not strictly on the point. I will leave it in anyway because, as we like to say here, the best people.)

This model of a modern member of Congress was joined by other fine legislators such as conspiracy theorist and 2001 Arizona Dentist of the Year Rep. Paul Gosar, Rep. Greg Steube (R-Mens Wearhouse), and avowed Christian Nationalist, coup supporter, and prolific misrepresenter of his educational history Rep. Andy Ogles (R-TN). There are many, many other GOP Congresspersons who seem to have been happy, even eager, to sign on to this bill.

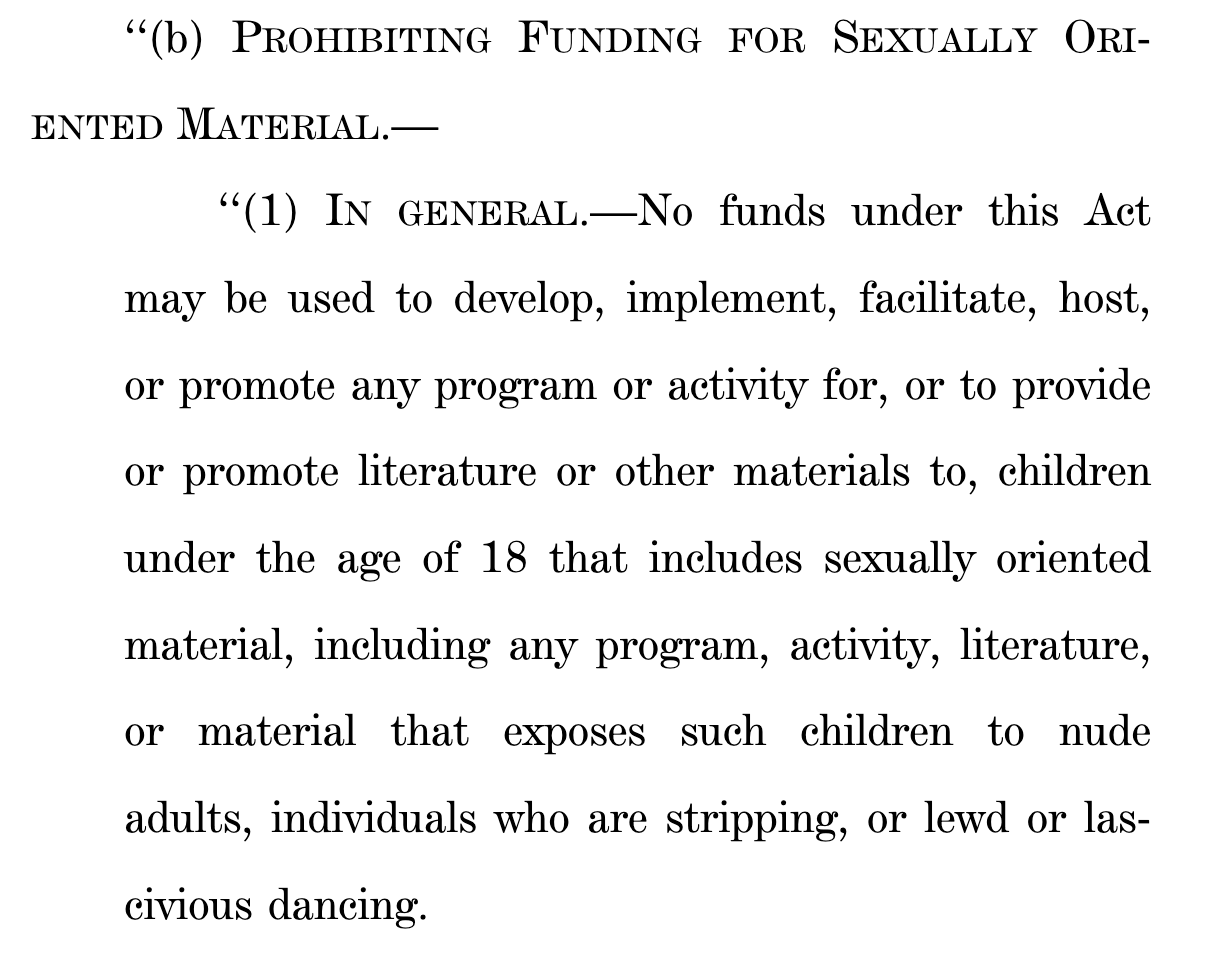

This lineup should give pause, but not as much as the language of the bill itself, which they have decided should be called the ‘‘Stop the Sexualization

of Children Act.’’ The bill would prohibit the use of funds to “develop, implement, facilitate, host, or promote any program or activity for, or to provide or promote literature or other materials to, children under the age of 18 that includes sexually oriented material.”

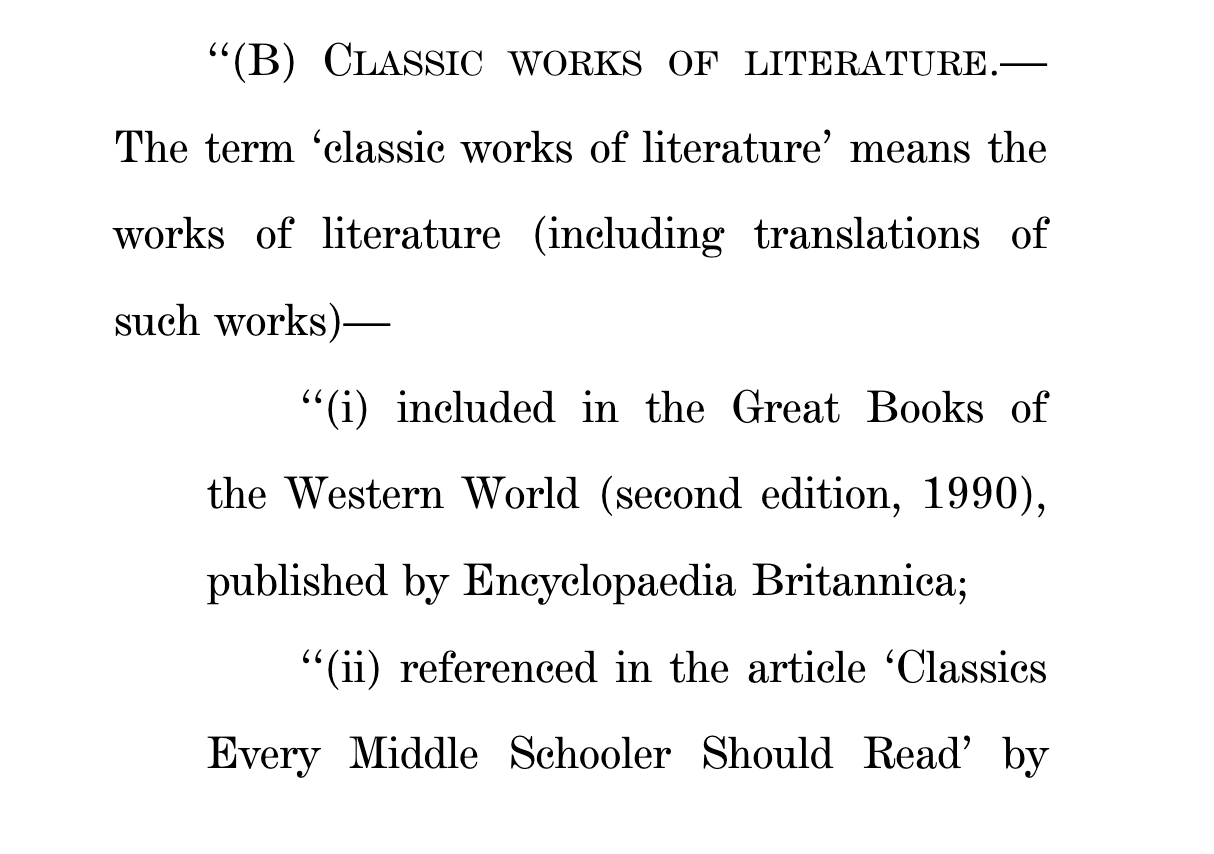

IN GENERAL, this is insane. No program, activity, literature or material–so anything–that exposes minors to naked grown-ups, to stripping individuals (groups are okay then), or to lewd or lascivious dancing. It has carve-outs for science and (of course) for religious texts. And for what it calls “classic works of literature.” How are those defined, you ask?

(director of the Creationist film Is Genesis History?, self-described “creative filmmaker who develops unique learning resources intended to advance the Kingdom of God,” podcaster at something called Modern Christian Men, and educator at Compass Classroom, a creator and purveyor of video classes which, it tells homeschooling parents, will “teach your kids to think Biblically about the world”)

I do not want to know anything about the relationship between Thomas Purifoy, Jr. and Mary Pierson Purifoy. What I know about them individually–he went to Vanderbilt, was a Navy Officer, and taught at the American School of Lyon and she was homeschooled until she graduated from high school (is how Compass puts it) in 2020, and then studied at a couple of institutions of higher education and possibly earned a degree from one but Compass leaves it ambiguous for some reason–is enough. What I do want to know is which legislative genius thought that a thirty-six year old encyclopedia and two articles published on a homeschooling video website by these two people should be deciding for the nation what constitutes our literary canon and so what gets excused for including “sexually oriented material.” Not to mention that the Supreme Court has never decided whether something merits not being banned if it’s “classic” or not but by whether it has literary merit.

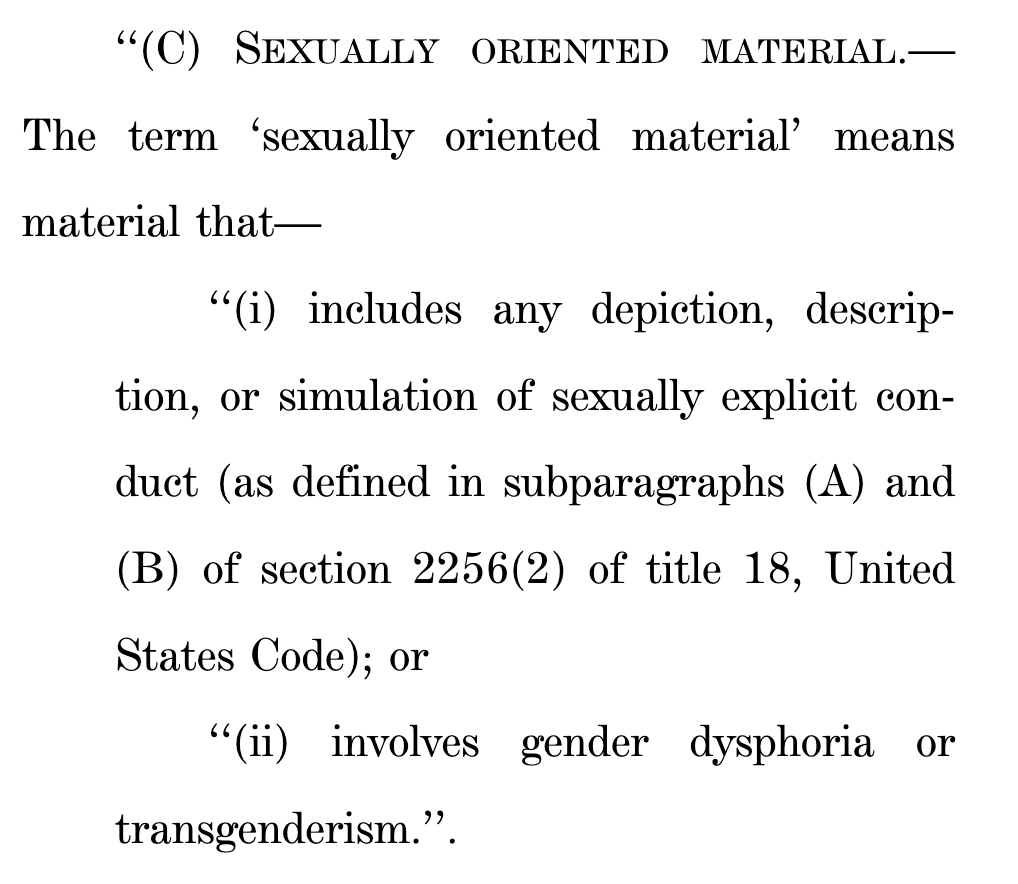

But enough about that, pal, you say, tell us how they define “sexually oriented material”! Fine!

I’m not looking up those subparagraphs. I could probably find them–I would certainly know them when I saw them, to make a Justice Stewart pun–but we already know the gist. There’s something that strikes me about this last bit, though, which ends this very short bill, and that’s the “or” at the end of (i), transitioning, if you’ll pardon the term, to (ii). I’m no lawyer, or legislator even, but it does seem to me that under this bill something falls under “sexually oriented material” if it’s explicit or if it “involves” anything about trans people. Tell me if I’m wrong, members of the bar or people at a bar, I don’t care, but I’m not.

So, to recap: a member of Congress known for approvingly quoting Hitler, for mistaking Sikhs for Muslims and objecting to both, and for working to curtail the rights of trans people got together with some like-minded friends, and said “Let’s put on a (national anti-LGBTQ-but-especially-T censorship) show!” and they recruited the finest Christian Nationalist homeschool educator minds of their generation to help them. Am I missing anything?

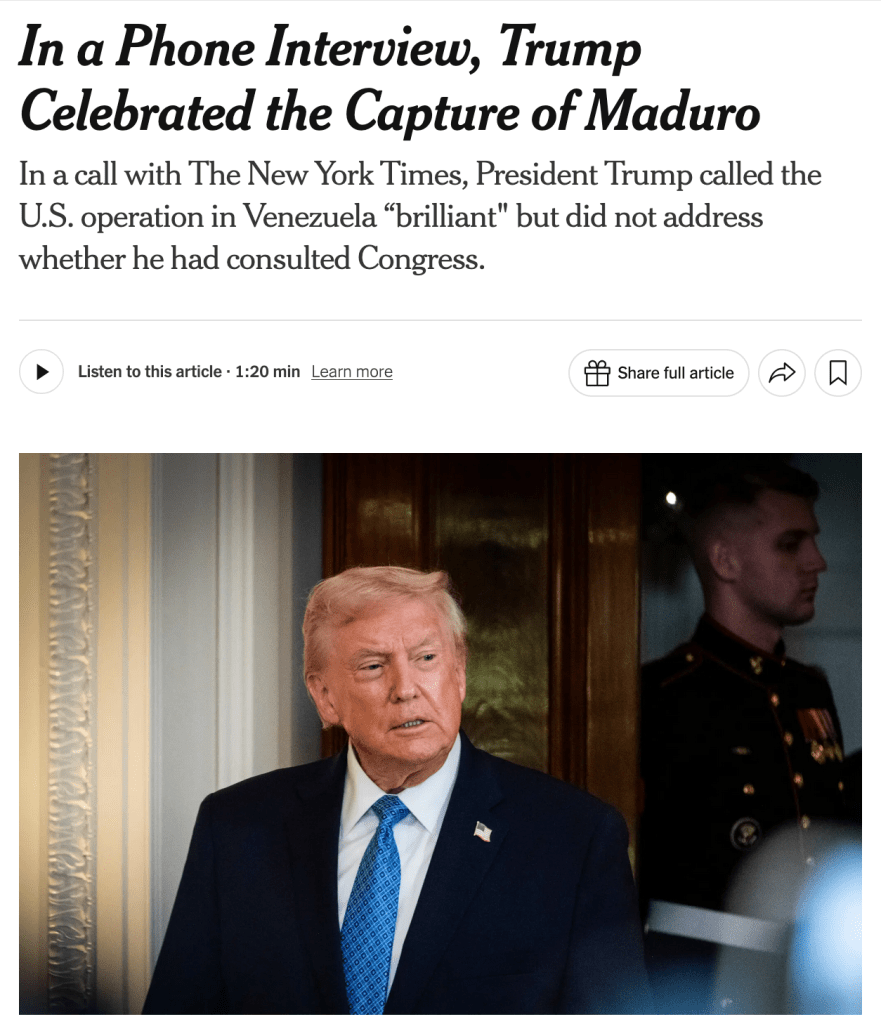

The most alarming thing about this all is the national part. The national anti-DEI campaign by executive order has stalled in the courts, but it’s done its damage. What will happen if we have a national effort, put into law, that tells us what we can’t teach, what we can’t lend, what we can’t learn? What will happen when the next law is about race? Religion? Political beliefs? Yesterday we learned that we’re moving one step closer to effectively having state media. Are you okay with that? With these people controlling what is said and known?

Yesterday in my Missouri Writers class (full title this semester–“Missouri Writers: Race and Class in Missouri”) I taught some poems by Langston Hughes and Sterling A, Brown, writer who stretch the definition of Missouri Writers by quite a bit–Hughes was born in Joplin but grew up elsewhere, Brown taught for a few years at Lincoln University in Jefferson City but otherwise lived and worked in other parts of the country–but we’ve been reading about race in nineteenth century Missouri and the country, and after we read Eliot and Marianne Moore (Kirkwood’s own!), I wanted to pick up the thread again. So we looked at a Jacob Lawrence painting from his Migration series and we listened to a minstrel performance of “Dixie” and we talked about the world these poets grew up in, to give some context for some difficult poems. But by the end of class, I saw on my students’ faces that it had been too much–too many hard-to-stomach poems about being Black in America in the early twentieth century, too many poems about lynching for one class meeting. So I apologized to them, but made clear that I didn’t think it was wrong to ask them to read these poems, and I didn’t sense that they disagreed. What’s going to school for if not to learn about the place you’re growing up in, other of course than becoming the AI-trained employee the future requires?

I don’t know what World Book or Compass Classroom has to say about whether these poems are classics, but I know there are people out there challenging books that are about the history and present of race in the US, people who would love a national law banning them. Just like there are people this week filing a bill to stop students from reading about trans people. Call your representative, your senator, any elected whose staff will pick up the phone, and tell them what you think about this. Read the new book I edited, Banning Books in America: Not a How-to. It came out a week ago, back when the laws to be angry about were state laws, five days before H.R. 7661 was filed. Rep. Mary Miller and the gang have decided to put on a show and take it national. It’s in previews. Let’s shut it down.