Ever feel like you’re being sold a bill of goods?

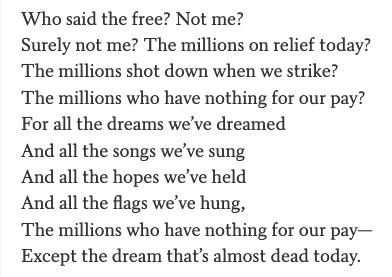

Excerpts from two emails that landed in my inbox yesterday:

The first is from an email helpfully sent to me by McGraw Hill GO, which as the name shouts, is raring to GO to sell me a product that will help me teach, ostensibly. I mean look!

It’s an eBook+! It lives within my LMS! It makes it easier to keep up with student progress and direct attention where it matters most, which is apparently somewhere other than whether my students are learning! I guess I should be grateful for that assurance of knowing my students are completing the reading, but instead I’m checking to see if I still have my wallet. Can I drive this eBook+ off the lot right now?

It’s the AI that I should apparently be most grateful for, though. The embedded generative AI learning tool, I am told, will create a more flexible learning environment! And that environment will drive meaningful engagements! It will also drive a deeper conceptual understanding, as opposed to some other kind of understanding, of my course content! So much driving! So much cause and effect! Instead of the hard and messy work of trying to help my students understand the things they read, the world around them, and themselves and their place in it, all I have to do is sit back and let GO drive. Whew. What a relief.

The second email comes from the Teaching for Learning (?) Center at my employer, This University in Canada, You’ve Never Heard of It. A featured speaker at an upcoming event will be the AI expert whose identity I have tried to disguise for some reason. This person will be coming to This University (TU, go fight win) to share with us the Good News of AI, sharing the εὐαγγέλιον, the gospel, that artificial intelligence has risen and will be our salvation. Do you believe in the Good News? It believes in you!

It’s the end of a long and cranky week, so forgive me the sarcasm. I’m not here to impugn motives of publishers, staff, or administrators or to criticize fellow instructors for wanting a break from the difficult work of teaching. I’m sensitive to the privilege I am lucky to enjoy of working at a research-intensive university, where, if I want, on a Friday afternoon during under-attended office hours, I can take a half hour and blog my thoughts into the abyss, and I’m sensitive to the four-four or more load of many instructors, for whom in my textbooks I have selected readings (and written apparatus supporting them) in order to lessen that load.

(prompt: “teacher being buried by papers”)

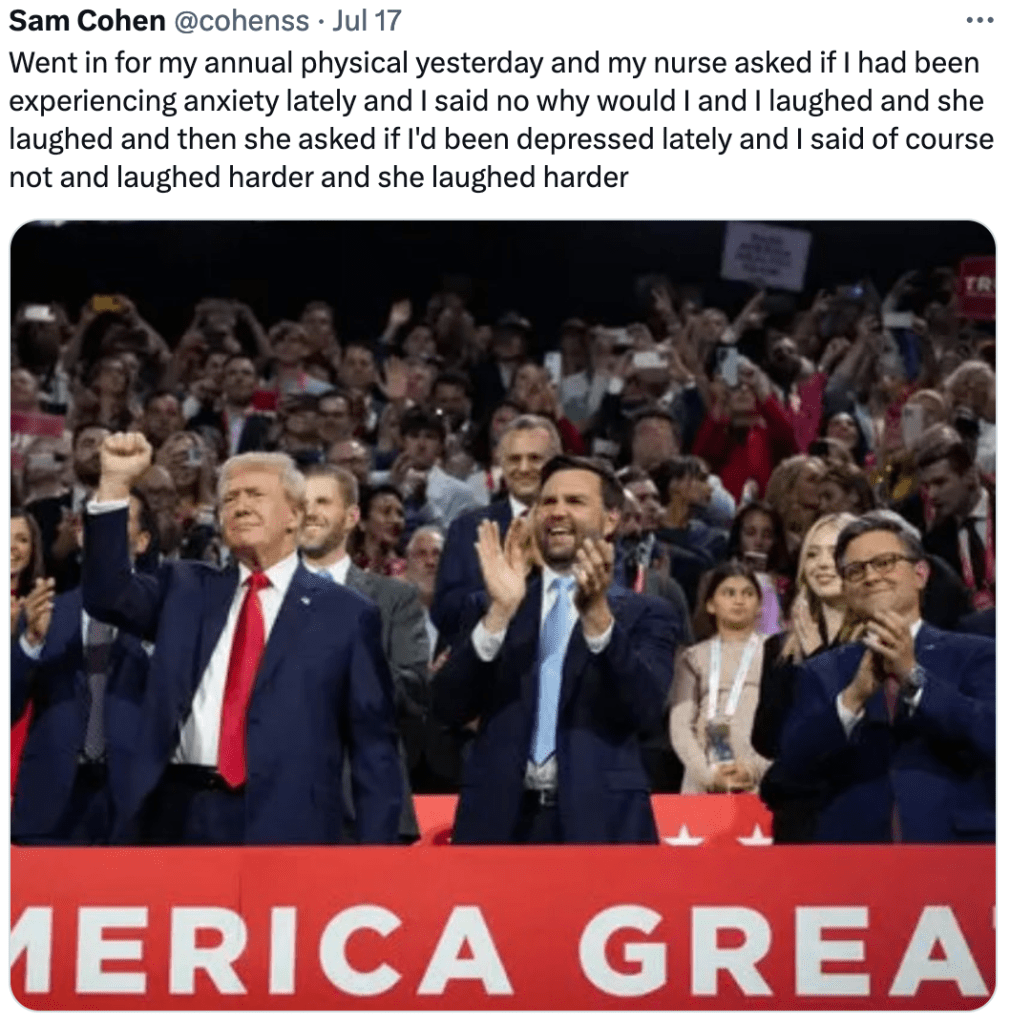

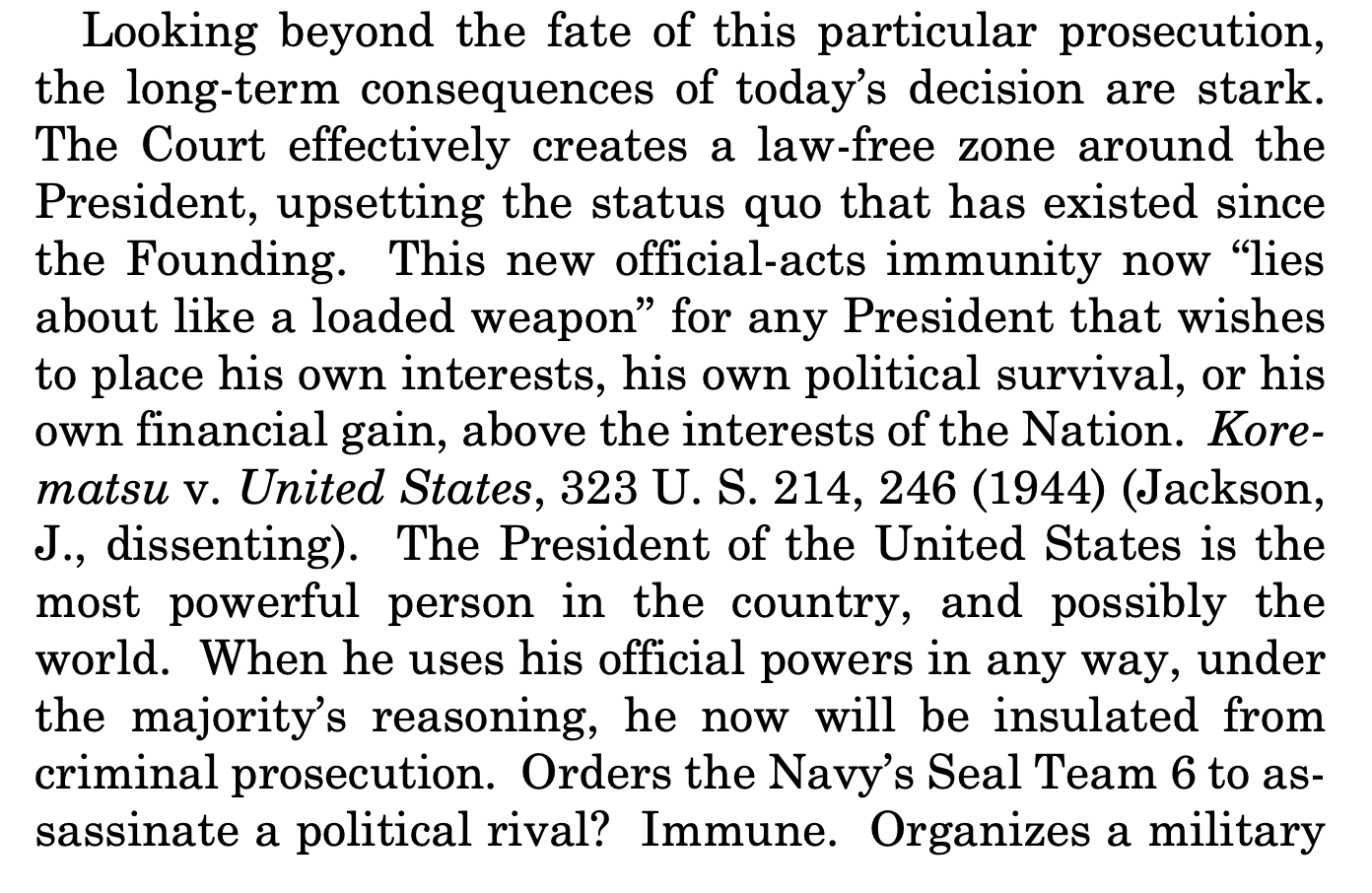

What I’m doing here with this spare half hour is saying that these claims of AI’s salvific power makes me feel like I’m being sold a bill of goods. The educational publishing company is in the business of selling things to help educators, and can hardly be faulted. It’s what it does. It has to keep swimming or it dies, or something. The whole world of ed tech (ET, by decree and henceforth) is in the same business. TU and by extension higher education are most emphatically not in the same business as EdTechpreneurs, and should not be the gullible rubes who snap up its latest products. Universities have been busy establishing a sorry track record of diving headfirst into the latest ET innovations–remember MOOCs?–and moving on from them once their promise went unrealized, leaving behind a trail littered with spent money and damaged morale.

I don’t want to overstate. I wouldn’t be so rash as to condemn everything about LMSes (how do you pluralize an acronym that ends in S? Why are my office hours today so quiet? Does it have anything to do with it being homecoming weekend?). As we learned during the pandemic, they make some things easier. But they can’t be used to replace us.

There is considerable pressure on higher ed administrators to cut costs, and as anybody who’s looked at university finances knows, one of the only places they can cut is instructor pay and benefits. It’s why you see departments shrinking as retired tenured faculty go unreplaced; it’s why you see whole departments razed if administrators can’t wait patiently for faculty to die off or at least go away. Contingent laborers cost less. ET promises lower costs. Humanities instruction, at least, what I do, is labor intensive. Human labor intensive. Humanities departments are forever being berated for the high costs of small classes (discussions which seem never to touch on the rarely mentioned high overhead incurred by the research grants given the big-lecture-teaching faculty in other disciplines, but that’s another discussion). The value of what we do lies in helping students learn to think, creatively and critically. We want to help them learn to be able to process large amounts of complicated information, to grapple with sophisticated concepts, to know when they’re being sold a bill of goods.

I don’t want resource-gobbling AI to transform the images in my head. I want to do it myself because part of the reward of creative thought and expression lies in the doing of it. I want my students to learn this. I don’t want TU or any other institution of higher learning to try to save money by outsourcing the work of education; in the end it will waste both the money it spends and the opportunity for students to learn to want to come up with interpretations, solutions, expressions. I got my first AI generated assignment this week. I read it. I knew instantly where it came from, and it was confirmed by an abashed student, and it sucked. It didn’t know anything, and it didn’t think anything, and it didn’t express anything.

My office hours are over. Monday morning I’ll come back to campus. At noon, my students and I will discuss the upsetting ending of Toni Morrison’s upsetting and beautiful novel The Bluest Eye, and we will talk about the history of it being banned around the country and in the town some of them come from by people who don’t value the kind of education that involves reading upsetting and beautiful things, and we will probably also talk about homecoming weekend and think about what universities are for, which I am always trying to get them to do because the whole point is to get them to look around and think about where they are, whether “there” is their classroom or university or state or country or planet. (They will also get good paying jobs because they know how to read and think and express their thoughts but can we please not let that be the only reason we do this?) I will try to drive meaningful engagements, if you want to put it that way, and appreciate the opportunity I have been given to do this important work the way I think most effective. Also I use much less water.