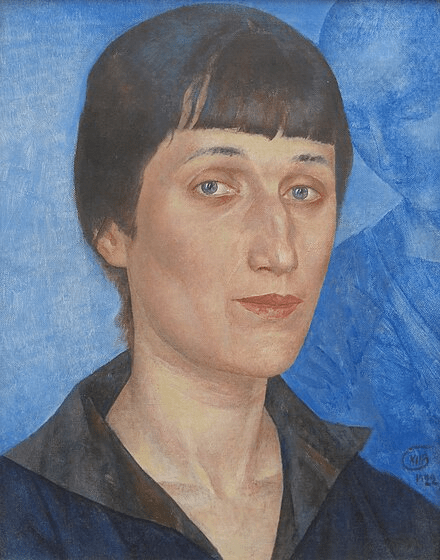

Anna Akhmatova

This set of poems was written by Anna Akhmatova from 1935-1961. Most of the poems were written in the 1940s, but Akhmatova did not think it would be safe for her to publish them at the time. They weren’t published in Russia until 1987. The below steals from a few different translations I could find on the internet (my favorite, Judith Hemschemeyer’s, is in the Norton World Lit but not online).

I wanted to post a version of Requiem tonight. Something about the last few weeks makes me want people who don’t know it to read it and people who do to read it again. I’ve been trying and trying to “describe this,” in Akhmatova’s words, to write about what’s happening to my country, and I will have to find a way, but for now the poems of a mother whose husband and son were jailed in another country, who had to memorize (rather than write out) her poems about the nightmare her country had become in order to stay out of prison herself, will have to do.

We’re not as far from this as we think we are.

No. Not under the vault of a foreign sky,

nor carried by a stranger’s broad wings —

in that time I stood with my people,

there, in our gray and unfortunate land.

— 1961

Instead of a Preface

In the terrifying years of Yezhov terror I spent seventeen months in

the prison lines of Leningrad. Somehow, at some point, someone

“recognized” me.

Then the woman standing behind me, her lips blue in the cold

light, a fellow sleepwalker who had certainly never heard my name

before, woke from her fetters and whispered in my ear (there, everyone

spoke in a whisper):

— And this? Can you describe this?

And I said:

— I can.

Then something resembling a smile slipped across the apparition

that only a moment before had been her face.

Dedication

The mountains kneel before our tragedy,

the great river is silenced at its source.

But our sorrow cannot break the prison locks;

behind them, despair tunnels endlessly on.

Will the spring breeze caress your face?

Will the sunset gently reveal you?

Not us. Our prison stretches to the sea:

everywhere the scream of key on stone

and the slogging stamp of soldiers’ boots.

We rose, as if for early Mass, and trudged

amid the tombstones of our ruined capital,

to face each other, more lifeless than the dead;

the sun sank low, the Neva misted,

and hope’s song came only on the wind.

The verdict. . . and she cries out,

suddenly alien, torn from the crowd,

as if life were ripped directly from her chest,

as if thrown to the floor, brutally, in haste.

But she continues . . . staggers on . . . alone . ..

Where are they now, my shadow friends

from those two years in hell?

What visions are theirs in the blind Siberian wind?

What do they see in the dim halo of the moon?

Will they hear this, my last farewell? My final greeting.

Prologue

Only a corpse could smile,

content, finally, to rest.

And like a useless appendage,

Leningrad swung from its prisons.

Mad from torture, contorted regiments

marched around the prisons’ naked walls

while farewell songs wailed

from train horns.

Stars of death stood above us

as innocent Russia cringed

beneath bloody boots

and the tire-tread of Black Marias.

1

They took you at dawn.

I followed, as if in a funeral procession.

In the dark pantry, children cried.

Before the Virgin Mother, a candle

drowned in its own wax.

Your lips were chill from the icon’s kiss.

The death-sweat on your brow . . . indelible.

Like the wives of Imperial Archers,

I shall stand howling under the Kremlins towers.

2

Quietly flows the quiet Don;

into my house slips the yellow moon.

He enters with his hat askew,

sees his shadow, that yellow moon.

This woman is sick to the bone,

this woman is sick and alone;

her husband dead, son shackled away.

Pray for me . . . for me, pray.

3

No. It is someone else who suffers.

I could not bear such pain. It isn’t me.

Shroud it in black; have the moon eclipse it.

Let them carry the torches away. . .

Night.

4

If I showed you, you silly girl,

beloved prankster, my merry

little sinner from Tzarskoye Selo,

what will happen to your life —

How three-hundredth in line, with a parcel,

you would stand by the Kresty prison,

your fiery tears

burning through the New Year’s ice.

See yourself at that silent dance, fixed

amid the sway of prison poplars. No sound.

No sound. Yet how many innocent lives

are ending...

5

Seventeen months I have screamed,

calling you home to me.

I threw myself at your executioners feet,

my son, my fate, my horror.

This moment is an infinite puzzle,

without solution, no, never for me:

man and beast, indistinguishable, crawling.

How long will I await this execution?

Only dusty flowers remain,

and the quiet censer, smoking;

and footprints that lead to nothing.

The immense star looks into my eyes

threatening, threatening: a promise

of ready death.

6

Time flies on, nearly weightless;

what happened, I don’t understand.

This city’s white nights peered

in on your prison cell; O, how again they watch

with a hawk’s burning eyes: pale nights

speaking of your lofty cross

and of death.

7

The Sentence

And the stone word fell

on my still living breast.

It is all right. I was ready for this,

after all. I’ll get by. Somehow...

I have the distraction of my chores:

I must destroy my past. Finally.

I must petrify my soul, then somehow

learn to nurture what remains —

Be that as it may... summer rustles

like a celebration outside my window.

I could smell it coming on the wind:

this sunny day; this empty house.

8

To Death

You will come in any case — why not now?

I am waiting for you—I cannot take much more.

I turned off the light and opened the door

for you. For you, so simple. And so strange.

Come to me, take any form you please:

burst through me like deadly hail;

strike me from behind like a weary thief;

fill my lungs, let me choke on your typhus gas.

Or recite the fairy tale you concocted: That little story

which makes us all sick; your mouthful of churned vomit —

so again I see the top of a policemans blue hat

and the caretaker, pale and trembling with fear.

It makes no difference. The Yenisei roils,

the North Star shines, and they will not cease today.

But the last horror is setting

in my beloved's sea-blue eyes.

9

Already the wing of madness

has shadowed half my soul,

held fiery wine to my lips,

and drawn me into its black valley.

I knew that to this devil’s wisdom

I must acquiesce: with tired ears

I listened to my garbling tongue,

then translated my own voice.

It says I may not take anything

along on my journey

(no matter that I politely ask

... no matter that I grovel) —

Not the fear of my sons face —

his paralyzed suffering — not

the day of that thunderous word,

nor the hour I met him in shackles.

Not his dear, cool hands,

nor a linden’s restless shadow

touched by the murmuring wind,

nor his final words of consolation.

10

Crucifixion

“Don’t cry for me, Mother.

Can’t you see I’m in the grave?”

1

A choir of angels glorified the hour,

the gray sky turned to molten light.

“Father, why hast thou forsaken Me?

Oh, Mother, please don’t cry for Me.”

2

Mary Magdalene tore at her breast, sobbing;

the beloved disciple watched Him, petrified.

His Mother stood away from them, immersed

in her own silence, where no one dared glance.

Epilogue

1

I learned how faces collapse under the weight

of a century, how terror peeks out from eyelids

cracked like stone tablets, and cuneiform suffering

etches its stony language on hollowed cheeks.

How a lock of cherished hair may turn

from black and gold to hasty silver;

how smiles wither on resigned lips,

and terror becomes trembling laughter.

I’m not praying for myself alone,

but for everyone who stood there with me

in crippling frost, and in July’s gnawing heat

before that blind red wall.

2

Again, the hour of remembrance draws near.

I see, I hear, I feel you; and I know them:

the fragile one we helped to the window,

the one who no longer wakes to her mother

land; and the girl who shook her beautiful hair,

saying, “I have come.” As if returning home.

I want to call out to them, each by name,

but the list that names them was stolen.

For them I weave a wide cloak

of shabby, eavesdropped words.

I remember them everywhere, always,

even in new troubles they are with me.

One hundred million people scream through

me, and if my tormented mouth is muzzled,

let them remember me as well, in my pen

ultimate moment, on my own remembrance day.

And if, by chance, this country should one

day decide to erect a monument to me, well

I graciously grant my permission.

But on these conditions: do not place

it by the sea, where I was born:

the sea no longer touches me;

nor plant it in the Tzarskoy garden, near

the sacred stump, where shades hunt me out;

but place it here, where I stood for three hundred

hours. Here, where the prison door will not unbolt

for me. Because I dread a peaceful death — for fear

I might forget the thunderous charge of Black Marias,

forget the arrhythmic drumming of fists on a door,

or the wounded howl of the old woman behind it.

So let the melting snow stream like tears

from the forged bronze eyes of my colossus,

while a prison dove coos from afar,

and ships glide silently along the Neva.